Making a difference

Fellows and alumni who have made a difference in the world

Back to Pioneering HistoryEmily Davies

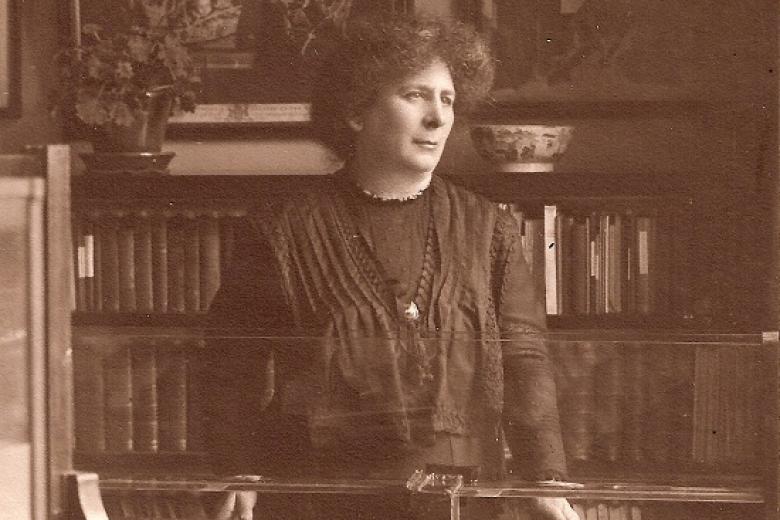

Emily Davies (1830–1921) was a suffragist, immersed in the mid 19th-century women’s movement. Her vision for women’s education, and her uncompromising commitment to excellence, inspired the foundation of Girton College. From 1872 to 1875, she was the fourth Mistress of the College, but drove its agenda from the foundation to 1904. In contrast to some of her peers, Emily Davies was tenacious in her insistence that women should study the same courses and sit the same exams under the same timetable as Cambridge men. In late 1872 and early 1873 the first Girtonians took Tripos examinations (unofficially). All passed, proving Emily Davies’s conviction correct.

Emily Davies

Emily Davies

Hertha Ayrton

Hertha Ayrton (1854–1923), born Phoebe Sarah Marks, was among the most influential British women scientists. A Girton student from 1876 to 1881, she was the first woman elected to the Institution of Electrical Engineers (1899); the first to read her own paper to the Royal Society (1904); the first (1902) nominated for election to that society (though barred by virtue of marriage) and the first to be awarded its prestigious Hughes Medal (1906). Practical as well as scholarly, she made many important discoveries, including the connection between current length and pressure in the electric arc. She registered 26 different patents and invented the Ayrton Fan – over 140,000 of these were distributed to disperse gas from World War One trenches. Hertha Ayrton’s success was underwritten by the early generosity of Barbara Bodichon (1827–1891), which enabled her to study Mathematics at Girton despite family hardship after the death of her father. This philanthropic history is continued in Girton today, thanks to a 1925 gift from her friend Ottilie Hancock (d. 1929) to endow the Hertha Ayrton Science Fellowship.

Hertha Ayrton in her laboratory, taken by J Russell & Sons, 1910 (archive reference: GCPH 7/3/3/2)

Hertha Ayrton in her laboratory, taken by J Russell & Sons, 1910 (archive reference: GCPH 7/3/3/2)

Ethel Sargant

Early visionaries such as Ethel Sargant (1863–1918) were an inspiration to future generations of students. Ethel Sargant came to Girton in 1881 to study Natural Sciences and went on to become an eminent botanist. Her best-known work concerned the anatomy of seedlings and the ancestry of angiosperms. Sargant was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1904 and was the first woman to serve on its council. In 1913 she was elected president of the Botany Section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In the same year she was elected to an Honorary Fellowship at Girton.

Ethel Sargant’s microscope now located in the Lawrence Room, the College museum.

Ethel Sargant’s microscope now located in the Lawrence Room, the College museum.

Barbara Bodichon

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891), artist, feminist, journalist and prominent campaigner for law reform and women’s rights was both a founder and a funder of the College. Unconventional, enthusiastic and charming, she was a long-standing friend of Emily Davies, and Girton’s largest early benefactor. She gave £1,000 to the initial fund, lent a further £5,000 in 1884, and then left the College £10,000 in her will in 1891. Though Barbara Bodichon’s generosity was crucial to Girton’s foundation and survival, her involvement went well beyond financial affairs. She took a particular interest in the health and comfort of the students and the decoration of the new buildings. Many of the paintings she donated still hang on the College’s walls today.

Portrait of Barbara Bodichon by Emily Osborn, not dated (archive reference: GCPH 11/33/31)

Portrait of Barbara Bodichon by Emily Osborn, not dated (archive reference: GCPH 11/33/31)

Sarojini Naidoo

Sarojini Naidoo (1900), one of the first Asian women, national poet and co-founder of the Congress Party in India.

Sarojini Naidoo

Sarojini Naidoo

Amy King

Amy King (1903), the first Black woman to study at the University of Cambridge.

Amy King

Amy King

Eileen Power

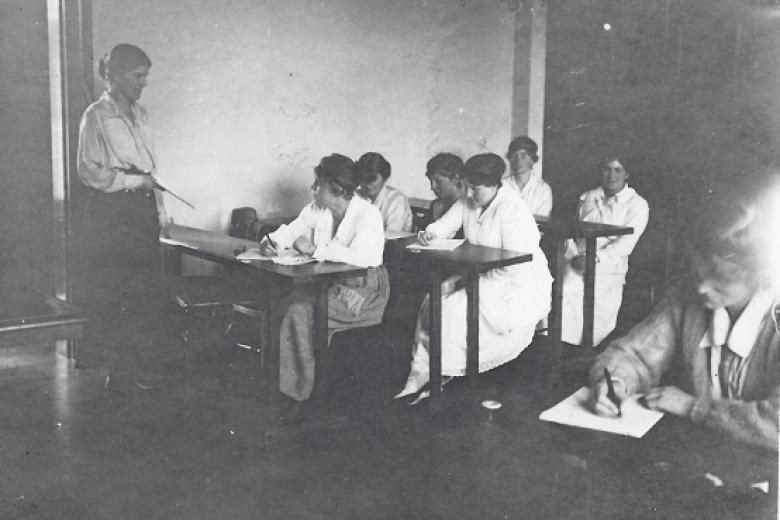

The medieval historian Eileen Power (1889–1940) was one of a series of remarkable historians who spent all or part of their careers at College in this period. Her predecessor and mentor, Ellen McArthur (1862–1927), was one of the first women to give Cambridge lectures in History attended by both men and women. One of Eileen Power’s successors as Girton Director of Studies was Helen Cam (1885–1968), who became the first woman full Professor at Harvard University when she took up the Zemurray Radcliffe Chair in 1948.

A student and Research Student at the College, Eileen Power was appointed Director of Studies at Girton in 1913. She had a stellar academic career, including appointment as a Professor at the London School of Economics, where she helped to reshape the economic history courses. Her many highly acclaimed publications included influential works on women’s history. She also gave memorable BBC Schools Radio broadcasts and wrote a series of history books for children, spreading ideas of internationalism. In 1938–1939 Eileen Power delivered the prestigious Ford Lectures in English History at Oxford University.

Eileen Power teaching in a classroom at Girton College taken by Bassano Ltd, 1919 (archive reference: GCPH 7/1/7)

Eileen Power teaching in a classroom at Girton College taken by Bassano Ltd, 1919 (archive reference: GCPH 7/1/7)

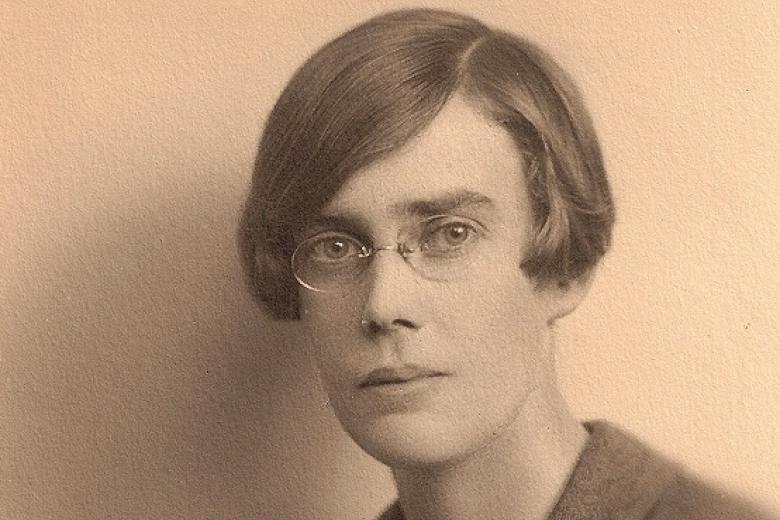

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Wrinch (1894–1976) was a mathematician and pioneering theoretical biologist. Her work included proposing the first-ever model for protein structure – the cyclol hypothesis – in 1936. The model proved controversial and was ultimately shown to be incorrect, but her methodology was pioneering and influential. Dorothy’s ground-breaking work and subsequent collaborations laid the foundations for discovering important clues to the drivers of protein folding – a question that remains at the forefront of biological research today.

Dorothy Wrinch entered Girton in 1913 on a scholarship to read Mathematics, where she excelled academically, achieving the status of a Wrangler. In 1920 she was elected Girton’s first Yarrow Research Fellow. She became the first woman in Cambridge to teach Mathematics to men and, in 1929, was the first woman to receive an Oxford Doctorate of Science (DSc). A friend of Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), she was a formidable philosopher of science, as well as a contributor to the work of Harold Jeffreys (1891–1989) on scientific inference. Most of all, though, she made a difference to scientific understanding of life itself, and to present-day research in molecular biology.

Dorothy Maud Wrinch, by Fremont Davis, 1937. Acc. 90-105 — Science Service, Records, 1920s-1970s, Smithsonian Institution Archives [https://www.flickr.com/photos/smithsonian/12484577685/in/album-72157614810586267/

Dorothy Maud Wrinch, by Fremont Davis, 1937. Acc. 90-105 — Science Service, Records, 1920s-1970s, Smithsonian Institution Archives [https://www.flickr.com/photos/smithsonian/12484577685/in/album-72157614810586267/

Medicine during the First World War

During the First World War, Girtonians made many significant contributions to the war effort, including caring for wounded soldiers in Britain and at the Front. One Girtonian war doctor was Mabel Hardie (1866–1916). Having studied Natural Sciences at Girton from 1887 to 1890, she trained as a doctor at Glasgow University, joined the suffrage movement and was jailed for taking part in its demonstrations.

On the outbreak of war, Mabel Hardie joined the Girton and Newnham Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH), serving near Troyes, in northern France. The Unit moved to Salonica in Serbia, where it faced an outbreak of malaria. Around this time, however, illness forced Mabel to return to London where she died of breast cancer.

Many hundreds of lives were saved by the courageous and talented women of the SWH. On 15 November 2014, as part of a national commemoration, the Last Post was played in Girton’s Stanley Library for Mabel Hardie as a representative of the fallen of World War One.

![Girton and Newnham Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals about to embark on board ship at Liverpool, October 1915 (reproduced courtesy of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow [https://heritage.rcpsg.ac.uk/items/show/408] CC BY-NC-SA 3.](http://www.girton.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/780x520_scale_crop/public/timeline-images/Making%20a%20Difference%20Timeline%207.jpg?itok=ozRM3T5d) Girton and Newnham Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals about to embark on board ship at Liverpool, October 1915 (reproduced courtesy of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow [https://heritage.rcpsg.ac.uk/items/show/408] CC BY-NC-SA 3.

Girton and Newnham Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals about to embark on board ship at Liverpool, October 1915 (reproduced courtesy of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow [https://heritage.rcpsg.ac.uk/items/show/408] CC BY-NC-SA 3.

Barbara Wootton

Barbara Wootton (1897–1988) was one of the most extraordinary public intellectuals of the twentieth century and made major contributions to British political life. A student of Classics then Economics at Girton from 1915 to 1919, in her final year Barbara Wootton obtained the highest marks awarded thus far in Part II of the Economics Tripos. In 1920, while Director of Studies at Girton, she became the first woman to deliver Cambridge University lectures in Economics.

Following her move into public life, key achievements of her later career include membership of four Royal Commissions, establishment of the successful campaign to rescue the recommendations of the 1942 Beveridge Report, helping to create the British welfare state and a period as a Governor of the BBC.

In recognition of her public service, in 1958 Barbara Wootton was among the first cohort of ten men and four women given a life peerage, and in 1967 she became the first woman Deputy Speaker of the House of Lords.

Studio portrait of Barbara Wootton, taken by Elliott & Fry Ltd, circa 1924 (archive reference: GCPP Wootton 1/4/1 pt)

Studio portrait of Barbara Wootton, taken by Elliott & Fry Ltd, circa 1924 (archive reference: GCPP Wootton 1/4/1 pt)

Joan Robinson

Many consider Joan Robinson (1903-1983) to be the most important woman in the history of economic thought, and certainly unlucky not to have been the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize (in Economic Sciences). Although she is often remembered as the originator of the theory of imperfect competition, she quickly rejected this work and immersed herself in the Keynesian ‘revolution’ of the 1930s, becoming one of its central figures. Her book, The Accumulation of Capital (1956), triggered one of the most acrimonious debates in the history of the discipline.

A controversial figure, she secured a number of public accolades, including appointment as the first economist on the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in 1948. A student at Girton from 1922 to 1925, and a Lecturer in the University from 1937, Joan Robinson was appointed a University Professor, and an Honorary Fellow of Girton, in 1965. Her name lives on in College through the Joan Robinson Economics Society and the Joan Robinson Research Fellowship in Heterodox Economics.

![Joan Violet Robinson by Walter Bird, 1959 © National Portrait Gallery, London [http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw162643/Joan-Violet-Robinson?LinkID=mp99820&search=sas&sText=joan+robinson&role=sit&rNo=1]. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 [https://creative](http://www.girton.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/780x520_scale_crop/public/timeline-images/Making%20a%20Difference%20Timeline%209.jpg?itok=eGcJMfA4) Joan Violet Robinson by Walter Bird, 1959 © National Portrait Gallery, London [http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw162643/Joan-Violet-Robinson?LinkID=mp99820&search=sas&sText=joan+robinson&role=sit&rNo=1]. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 [https://creative

Joan Violet Robinson by Walter Bird, 1959 © National Portrait Gallery, London [http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw162643/Joan-Violet-Robinson?LinkID=mp99820&search=sas&sText=joan+robinson&role=sit&rNo=1]. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 [https://creative

Kathleen Raine

Kathleen Raine (1908–2003) celebrated for her meditative, lyrical writing, received the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1992. She studied Natural Sciences at Girton from 1926 to 1929 (specialising in Psychology in her final year), and returned as a Research Fellow in 1955. As an undergraduate, Kathleen Raine had a major role in establishing an enduring tradition of poetry at Girton, and was one of two women student poets published in the new Cambridge magazine, Experiment. This was the prelude to a remarkable literary and poetic career, during which she published 17 collections of poems, and many works of prose.

In later life she co-founded the journal Temenos and established the Temenos Academy. A sculpture of Kathleen Raine, originally designed for HRH Prince of Wales’ sculpture collection at Highgrove House, stands in the Fellows’ Drawing Room today, overseeing regular meetings of the thriving poetry society.

Detail of photograph, showing Kathleen Raine on Gwithian beach, Cornwall, 1924 (reproduced courtesy of Judith Rodden – archive reference: GCPP Raine 2)

Detail of photograph, showing Kathleen Raine on Gwithian beach, Cornwall, 1924 (reproduced courtesy of Judith Rodden – archive reference: GCPP Raine 2)

1939 World War II and Bletchley Park

During the Second World War more than a dozen Girtonians worked at Bletchley Park, the top-secret British code-breaking establishment. Some paused their degrees to join the war-effort, others were recruited as graduates. The Official Secrets Act silenced Bletchley memories for many years, but in later life Girtonians would recall their work and lives in the Bletchley Huts. Some were machine operators, setting and re-setting keys on replica German ‘enigma’ machines; others listened to enemy radio broadcasts, tapping out jumbles of words and starting the deciphering; others focussed on decoding and analysis. Discussing work outside your hut was forbidden. Some recalled periods of boredom, others fascinating work spliced by fear that a small error could risk lives. A canteen meal – subject to rationing – was eaten on a rota governed by coloured tickets and billets, sometimes in neighbouring villages, were visited only to sleep – hard to get used to in daylight. Clothes might be washed before work, and left to dry on office radiators, and there were even on-base hairdressers and baths to maximise efficiency.

Bletchley Park personnel, at work in the Hut 6 machine room in Block D, probably early 1945 (image reproduced courtesy of Bletchley Park)

Bletchley Park personnel, at work in the Hut 6 machine room in Block D, probably early 1945 (image reproduced courtesy of Bletchley Park)

Gloria Carpenter

Gloria Carpenter (1948), the first Black woman to receive a degree from the University of Cambridge.

Gloria Carpenter

Gloria Carpenter

Leadership in Medicine

Although Medicine as an academic discipline has long been studied at the University, it was only in 1976 that the University’s Clinical School opened, with Girton Fellows, Professor of Radiology, Professor Thomas Sherwood and Dr Carol Seymour, Research Fellow, at its leading edge.

Girton also believed passionately that empathy for their future patients was as important as scientific academic excellence, admitting candidates from diverse backgrounds including one who left school at 14 years and others who read diverse subjects such as Music and Archaeology.

Building on the success of Girtonian doctors, such as Professor Wendy Savage (1953), Dr John Marks (1979) and Professor Sue Iverson (1958), several today are leading Presidents of UK Medical Societies, including:

- Professor Veronica Van Heyningen (1965) President of the Genetics Society.

- Dr Sarah Clarke (1984), President of the British Cardio-Vascular Society.

- Professor Lesley Regan (1985 Bye-Fellow), President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

- Dr Suzy Lishman (1986; 2019 Honorary Fellow) President of the Royal College of Pathologists.

The rod of Asclepius adapted for the Girton College Medical Society (created by Life Fellow, Peter Sparks)

The rod of Asclepius adapted for the Girton College Medical Society (created by Life Fellow, Peter Sparks)

Delia Derbyshire

Everyone has heard of the TV series Doctor Who. However, it is doubtful whether more than a handful of viewers watching more than 800 episodes over 36 seasons could name the person who mixed its pioneering electronic soundtrack. That person was Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) who came to Girton in 1956 where she studied Mathematics and then Music (both Medieval and Modern).

Shortly after graduating she joined the BBC and in 1962 was, at her own request, assigned to the Radiophonic Workshop. There, after her 1963 success with Doctor Who, she spent 11 years creating original soundtracks for almost 200 radio and television programmes. She is one of the earliest and most influential electronic sound synthesists, with a prodigious output that has shaped the industry.

Recently, her work has experienced something of a renaissance, and in 2017 she was awarded a posthumous honorary doctorate from Coventry University in her hometown.

Delia Derbyshire and Desmond Briscoe at work in BBC Radiophonic Workshop (© BBC Photo Library)

Delia Derbyshire and Desmond Briscoe at work in BBC Radiophonic Workshop (© BBC Photo Library)

Legal high flyers

Law students of the 1960’s and 1970’s formed an outstanding cohort securing some notable firsts in the legal world, including:

- Dame Rosalyn Higgins (1959, LLB 1962 and Harkness Fellow from 1959-61; 1996 Honorary Fellow) was the first female judge elected to the International Court of Justice, becoming President in 2006.

- Baroness Brenda Hale (1963; 1995 Honorary Fellow; 2004 The College Visitor) the first woman member, and then President, of the UK Supreme Court.

- Dame Mary Arden (1965; 1995 Honorary Fellow) was, in 1993, first female High Court judge to be assigned to the Chancery Division. Currently she serves on the Court of Appeal of England and Wales and is Head of International Judicial Relations for England and Wales.

- Dame Elizabeth Gloster (1967; 2011 Honorary Fellow), first female judge of the Commercial Court, is now a judge of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales.

Baroness Brenda Hale and Dame Rosalyn Higgins at the Girton150 Festival (2019)

Baroness Brenda Hale and Dame Rosalyn Higgins at the Girton150 Festival (2019)

Engineering the future

The glass ceiling of Engineering, traditionally a male-dominated profession, has been shattered by a string of notable Girton alumni, and stellar engineers in this period include:

- Professor Dame Ann Dowling (1970 Mathematics), is the first woman President of the Royal Academy of Engineering. She is a mechanical engineer who researches combustion, acoustics and vibration, focusing on how to reduce road vehicle and aircraft noise. In 1993 Dowling was appointed as the first female professor of Engineering (Mechanical) at Cambridge University where, from 2009 to 2014 she was Head of Department.

- Professor Sarah Springman (1975 Engineering; 2015 Honorary Fellow) is Rector (Head of Academic Affairs) at ETH Zurich, one of Europe’s top 5 Universities. She is also a triathlete, representing Great Britain from 1983 – 93, and becoming the President of British Triathlon.

- Professor Helen Atkinson (1978 Metallurgy and Material Sciences) was named as one of the UK Research Council’s Women of Outstanding Achievement 2010 for leadership and inspiration in science, engineering and technology, and awarded CBE in the 2014 New Year’s honours.

Ann Dowling (1970, Mathematics) in her former undergraduate room (F35) with the current undergraduate occupant. Photograph credit: Alastair Levy (2018)

Ann Dowling (1970, Mathematics) in her former undergraduate room (F35) with the current undergraduate occupant. Photograph credit: Alastair Levy (2018)

Creating literary waves

In this period we would highlight a number of eminent English scholars who held (or still hold) Girton Fellowships, including:

- Joan Bennett (1896-1986), (1916, Modern and Medieval Languages), Fellow 1953–63, published on the Metaphysical Poets.

- Professor Muriel Bradbrook (1909-1993), (1927), Mistress of Girton 1968–1976, whose scholarship lay in the field of Elizabethan theatre.

- Professor Anne Barton (1933-2013), (1954, English), an Elizabethan scholar, Research Fellow (1960–1962) then Fellow of Girton (1962–1972).

- Professor Dame Gillian Beer FBA, Fellow of Girton for over 40 years (Research Fellow 1965–1966, Fellow 1966–1989, Professorial Fellow 1989–1994, Honorary Fellow 1994), King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at Cambridge, later President of Clare Hall. Her scholarship lies mostly in the field of Victorian studies.

- Professor Gillian Mann, FBA, a Fellow since 1972, who specialises in medieval and Renaissance English, particularly the work of Chaucer.

- Anita Desai, Visiting Fellow 1986–1987, Honorary Fellow since 1988, Indian novelist and emerita John E. Burchard Professor of Humanities at MIT.

Bronze bust of Professor M C Bradbrook by Derek Batty (1991)

Bronze bust of Professor M C Bradbrook by Derek Batty (1991)

Celebrating teaching excellence

‘The experience of a Cambridge education is that of being taught by the best minds in your field, and having access to the knowledge of renowned academics as supervisors’ - Professor Marilyn Strathern, Fellow of the British Academy, Mistress 1999–2009.

Small group teaching is what makes Cambridge so special and Girton has created career positions for world-class educators. They work alongside colleagues from nearly every department in the University to inspire their students with a passion for learning and the courage to challenge ideas.

Twelve of Girton’s Fellows have become Pilkington Prize winners for teaching excellence. They include Josh Slater for VetMed (2003 winner), Julia Riley for Physics (2009 winner), Martin Ennis for Music (2009 winner), Hugh Shercliff for Engineering (2011 winner), Andrew Jefferies for VetMed (2011 winner), Nik Cunniffe for Plant Sciences (2015 winner), Sandra Fulton for Biochemistry (2016 winner), Jochen Runde for Management Education (2017 winner), Stelios Tofaris for Law (2018 winner), Stuart Davis for MMLL (2018 winner) Harriet Allen for Geography (2020 winner) and Stuart Scott for Engineering (2020 winner). Girton hosted the Pilkington Prize ceremony in 2019, during its 150th anniversary year celebrations.

Pilkington Prize Winners 2018 Dr Stelios Tofaris and Dr Stuart Davis

Pilkington Prize Winners 2018 Dr Stelios Tofaris and Dr Stuart Davis

Priscilla Mensah

Priscilla Mensah (2012) the first Black woman president of CUSU.

Priscilla Mensah (2012)

Priscilla Mensah (2012)

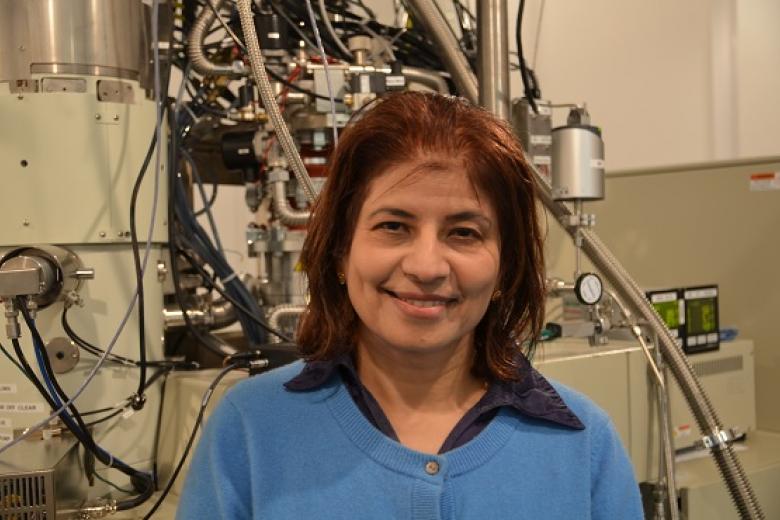

Women in science laureates

Professor Pratibha Gai (1971 Physics; 2019 Honorary Fellow) was one of four Girton L’Oreal-UNESCO Women in Science Laureates, who received her award in 2013. She won the award for ingeniously modifying her electron microscope so that she was able to observe chemical reactions occurring at surface atoms of catalysts which will help scientists in their development of new medicines or new energy sources. She said, ‘As a young girl I was always interested in the world we live in and science is the key to understanding it.’

The other Girtonian winners were Professor Frances Ashcroft (1971 Natural Sciences; 2011 Honorary Fellow), Professor Athene Donald (1971 Natural Sciences; 2011 Honorary Fellow) and Professor Philippa Marrack (1970 Immunology, Research Fellow). In addition to the eminent L’Oreal-UNESCO awards, Girton’s scientists have continued to win prestigious global awards for the transformational impact of their science.

Pratibha Gai, L’Oreal-UNESCO Women in Science Laureate, 2013

Pratibha Gai, L’Oreal-UNESCO Women in Science Laureate, 2013

Global pioneers

Girton alumni make a lasting difference to society through their leadership and innovation skills. Many are pioneers, breaking new ground in their fields of expertise. Notable global firsts include:

- Dame Zarine Kharas DBE (1970 Law) is the co-founder of the innovative Just Giving, now the world’s leading global online social platform for tax-effective charitable giving.

- HE Dame Karen Pierce DBE (1978 English; 2019 Honorary Fellow) became the United Kingdom’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York in March 2018, the first woman to be given this most prestigious post in the British diplomatic service since the UN’s formation in 1945.

- Lim Hwee Hua (1978 Engineering) was the first woman to serve in Singapore’s cabinet when she was made a Minister in the Prime Minister’s office in 2009. She is now an Executive Director of the private equity firm Tembusa Partners.

- Dawn Airey (1981 Geography), served as Chief Executive Officer of Getty Images from 2015 to 2019, the world’s leading visual communications company. Previously a Senior Vice President at Yahoo, Dawn Airey has over 30 years of experience in the media industry. Dawin is now Chair of the Barclays FA Women's Superleague and FA Women's Championship Board.

- Jane Fraser (1985 Economics) was the first woman Chief Executive of Citicorp Latin America, and will become the first woman to be Chief Executive of a Wall Street Bank when she becomes Chief Executive of Citi in February 2021.

Hwee Hua Lim with students from Singapore following her lecture ‘Navigating Asia – the role of government’ at Girton

Hwee Hua Lim with students from Singapore following her lecture ‘Navigating Asia – the role of government’ at Girton

Undergraduates

Postgraduates

Alumni & Supporters

- Give to Girton

- Alumni events

- Alumni community

- Publications

- Meet the team

- Merchandise

- Update your details

© 2025 Girton College is a Registered Charity, registered with The Charity Commission for England and Wales, number 1137541. Designed & built by Mobas.